The Collingwood Timeline

Admiral Lord Collingwood – a biographical sketch (Max Adams)

Collingwood – Northumberland’s Heart of Oak (Max Adams) – audio book

Cuthbert Collingwood’s Schooldays (Simon Tilbrook)

Collingwood at Trafalgar (Professor Eric Grove)

21st October 1805, 0800 hours: and now, the Shipping Forecast…

Lord Collingwood’s links with Menorca

A tribute in song (Pete Wood)

The Great Man’s Own Words

And Others on Collingwood

The Collingwood Timeline

(Time in Newcastle and Morpeth in bold, at sea or seeking a ship in London in ordinary).

In Newcastle 1748-1761:

1748 – Cuthbert Collingwood born on 26th September in a house on the Side, Newcastle.

1759 – Attends Royal Grammar School.

At sea or seeking another ship in London – 1761-1786:

1761 – Goes to sea, along with his brother Wilfred, as a ‘follower’ to his uncle Captain Richard Brathwaite. They join the 28 gun frigate Shannon.

1762 – Follows Brathwaite to the 24 gun frigate Gibraltar. Serves in Home and Atlantic waters and makes his first voyage to the Mediterranean.

1766 – Rated midshipman.

1767 – Transfers to 28 gun frigate Liverpool, still following Brathwaite.

1770-71 – Rated master’s mate by this date. Starts log of cruise in the Mediterranean on 8th December 1770 as Liverpool sails towards Menorca. Cruises in Mediterranean through 1771.

1772 – Transfers to Portsmouth guardship Lennox, under Captain Robert Roddam, a fellow Northumbrian and family friend.

1773 – Transfers to 50 gun ship Portland and sails to the West Indies. Meets 15 year old Horatio Nelson for the first time. Transfers to 80 gun ship Princess Amelia and sails up the East Coast of America before returning to England.

1774 – Arrives in Boston, Massachusetts in July 1774 as master’s mate aboard 50 gun ship Preston.

1775 – 17th June 1775 – Commands second wave of boats for the amphibious attack on Bunker’s Hill and distinguishes himself by his coolness and bravery. Promoted Acting-Lieutenant.

1776 – Returns to England aboard 64 gun ship Somerset. Promotion confirmed, but he stays in London to seek another appointment to a ship. Appointed to 14 gun sloop Hornet and sails for West Indies.

1778 – Replaces Nelson in the 32 gun frigate Lowestoffe, then in the 50 gun flagship Bristol.

1779 – Twenty year old Nelson promoted post-captain to the 28 gun frigate Hinchinbroke. Collingwood replaces him as master and commander of the 14 gun brig Badger.

1780 – Nelson sent home to recover from illness. Collingwood promoted post-captain in Hinchinbroke to replace him.

1782 – Returns to England but probably stays in London seeking another ship.

1783 – Sails to West Indies as captain of 44 gun frigate Mediator.

1786 – Returns to England and leaves Mediator. Remains in London but fails to get another ship.

In Newcastle and surrounds approx. November 1786 – May 1790:

1786 – Travels north to Newcastle towards the end of the year.

1787 – 21st April, Collingwood’s brother Wilfred dies at sea in the West Indies.

In London seeking a ship or at sea May 1790 – May 1791:

1790 – In May Collingwood is in London seeking another ship. First mention of a dog, that may be Bounce. In June he is appointed to the 32 gun frigate Mermaid. In October Mermaid is at Portsmouth waiting to sail to the West Indies but now Collingwood doesn’t want to go because he has reached an understanding with Sarah Blackett and is anxious to be married! Sails for the West Indies soon after.

1791 – Returns to Portsmouth in April, but has to remain in Portsmouth until the ship is repaired and the crew paid off.

In Newcastle, Morpeth and surrounds May 1791 – February 1793:

1791 – 18th June 1791, marries Sarah Blackett at St. Nicholas’ Cathedral, Newcastle.

1792 – Cuthbert and Sarah rent a house in Morpeth.

1792 – May, birth of daughter Sarah.

Mostly at sea or seeking a ship in London February 1793- February 1799 apart from two short trips to Morpeth in 1794:

1793 – February, returns to London to seek a ship.

1793 – Appointed as flag captain to Rear-Admiral George Bowyer on board 98 gun ship Prince.

1793 – August, birth of second child, Mary Patience.

1794 – Transfers to the 98 gun ship Barfleur and takes part in the Battle of the Glorious First of June.

1794 – Short trips to Morpeth in July and October to visit his family.

1795 – Takes command of 74 gun ship Excellent. Sails to the Mediterranean.

1797 – Feb 14th takes major part in the victory at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, coming to Nelson’s aid at a critical point of the battle. Receives a gold medal for his efforts and a belated one for the Glorious First of June.

In Morpeth February 1799-June 1799:

1799 – February. Returns to Morpeth and is promoted to rear-admiral of the white.

At sea mostly blockading the French in the Channel June 1799-May 1802:

1799 – June. Blockading the French with the Channel fleet in the 74 gun ship Triumph.

1800 – Transfers to 98 gun ship Barfleur. Blockade continues with home base being Plymouth.

1801 – January. Promoted Rear Admiral of the Red. Sarah and little Sarah visit Collingwood in Plymouth at the end of the month but Collingwood is able to spend less than a day with them before he is back at sea. They remained in Plymouth through the spring and summer and he was able to spend a few more days with them when he returned to port at the end of March and after other cruises.

1801 – Purchase of house in Morpeth, which the Collingwoods had previously rented.

1802 – March. Peace of Amiens.

In Morpeth May 1802-May 1803 – (he never returns after this):

1802 – May. Collingwood returns to Morpeth and begins to make improvements to the house. He enjoys growing vegetables and taking walks in the Northumberland countryside. Accompanied by Bounce he plants acorns as he goes.

At sea May 1803-March 7th 1810:

1803 – May. War declared with France and Collingwood returns to the blockade of the French.

1804 – April – Promoted to Vice Admiral of the Blue.

1805 – Blockade of Cadiz.

1805 – 21st October. Battle of Trafalgar. Collingwood leads the lee column into action in the 100 gun ship Royal Sovereign. Death of Nelson. Collingwood takes command and completes the victory.

1806 – Now Baron Collingwood of Caldburne and Hethpool, Vice – Admiral of the Red and Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean. Continues to blockade Cadiz.

1806-10 – Military and diplomatic activity throughout the Mediterranean.

1809 – Transfers to his last ship the 110 gun Ville de Paris.

1809 – Death of Bounce, who fell overboard during the night.

1810 – 3rd March hands over his command due to ill health. 6th March sets sail for England in Ville de Paris. 7th March Death of Admiral Lord Collingwood.

1810 – 11th May. Buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

(The above assembled with the kind assistance of Tyne & Wear Museums)

Return to TOP OF PAGE

Admiral Lord Collingwood: a biographical sketch

Cuthbert Collingwood was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1748 into a large family, the eldest of three sons. The Collingwoods were an old Northumbrian family, though the Admiral’s father, also Cuthbert, was a trader without land or fortune.

The building in which the family lived, on the steep, narrow street called The Side, which leads from St Nicholas’s Cathedral down towards the Quayside, has long gone. But above the doorway to Milburn House, just below the Black Gate, a plaque and a bust record its location. The castle and the city’s walls are a continuing reminder that the Newcastle of Collingwood’s day was still a border garrison whose gates and walls had been manned as recently as 1745 against the Jacobite rebellion.

But Newcastle was also an international city of trade. The Quayside bustled with shipping from across the world. Coals from the North-East’s apparently inexhaustible mines were exported across the seven seas and in return came exotic spices from the Far East, tobacco from America, tea from India, sugar and rum from the West Indies.

But above all, and almost more precious than goods, was news — from Canada and Hanover, from Stettin and Petersburg and the Cape. Britain, flexing her imperial muscles as never before, was at the centre of the world and the imaginations of young boys growing up here were fired by the exploits of daring naval captains and heroic generals.

The oldest son of a trader might have been expected to follow his father into business. But the business was failing. The Collingwoods used their family connections to procure for Cuthbert and his brother Wilfred berths as midshipmen in the Royal Navy. Thus ended the future Admiral’s short period of formal education at Newcastle’s famous Royal Grammar School, where he had already become friends with John Scott, the future Lord Eldon.

The Collingwood boys went to sea in 1761 at the ages of 13 and 11 respectively in the 28-gun frigate Shannon, commanded by Robert Braithwaite, a relative of Mrs Collingwood. As midshipmen they would be trained as future officers and gentlemen. They would serve a long apprenticeship, with at least six years before they could be considered for examination as lieutenants. In Cuthbert’s case he did not become lieutenant until the age of 27, after seeing his first action — the amphibious assault on Bunker Hill near Boston which signalled the start of the American War of Independence in 1775.

The first of Collingwood’s legendary letters dates from this period, but his midshipman’s journals, one of which survives from tours in the Mediterranean and West Indies, shows that his character was fully formed at an early age. He was conscientious and a gifted seaman. He had mastered navigation, was cool and brave under fire. What is more, he was a compassionate and deeply humane officer who hated flogging and grieved when he lost a shipmate. He was also, like his much younger friend Horatio Nelson, whom he first met in 1773, ambitious and zealous for the honour of the navy and the King.

England’s future saviours first served together under Sir Peter Parker on the West Indies station in 1778. Nelson had achieved the rank of Post-Captain at the unusually young age of 20. Collingwood, now 30, was suffering as a lieutenant under a tyrannical and ineffective commander called Robert Haswell in the 14-gun sloop Hornet. Nelson persuaded Parker to bring Collingwood under his command, first as lieutenant in the frigate Lowestoffe, then as Commander in the brig Badger, and then as Post-Captain in Hinchinbroke. Because of the ladder system of seniority in the Royal Navy, Nelson would retain a few crucial months’ seniority over his friend up until his death at Trafalgar 25 years later.

Their first adventure together was disastrous. Nelson, on more or less his own authority, accompanied an army expedition up the San Juan River (in modern Nicaragua) looking for a new route to the Pacific Ocean and he nearly died of fever. Collingwood, stationed at the mouth of the river in support, lost 180 of his 200 men to malaria and the ‘yellow jack’. Nelson returned almost lifeless to England. Collingwood remained in the Indies and survived shipwreck in a great hurricane off Jamaica in 1781.

Nelson’s and Collingwood’s lives seemed intertwined. In 1784 they were stationed together again in the West Indies. Collingwood was based at English Harbour in Antigua, charged with stemming the now-illegal trade between the islands and the new United States. His zealous enforcement of the so-called Navigation Acts won him few friends among the merchants of the Caribbean.

His consolation was the company of the navy’s commissioner in Antigua, John Moutray, and, perhaps even more, that of Mary Moutray, the commissioner’s wife. She was educated and intelligent, delightful company and a gifted hostess. When Nelson came out to join Collingwood these twin epitomes of England’s naval officer class were united in their determination to stamp out smuggling, and united in their affection for Mrs Moutray. She was eventually forced to return to England with her ailing husband, but the two men remained friends with her for the rest of their lives.

Collingwood himself returned to England in 1786 and spent the only significant period of his life ashore. A year after leaving the West Indies he received the devastating news in a touching letter from Nelson that Wilfred, his brother and fellow captain, had died of an illness. When he was not in London using his connections to try to get another ship (in peace-time there was tremendous competition for each command as much of the fleet was laid-up) he was at home in Northumberland. Such was the status of a captain in the Navy, and so impressive a man had Collingwood become after nearly 20 years at sea, that he was able to successfully court the daughter of the Mayor of Newcastle, Sarah Blackett, whom he married in 1791. They went to live in Morpeth, in the house that still bears his name on Oldgate on the banks of the River Wansbeck. They had two daughters, little Sal and Mary Patience. For the rest of his life Collingwood’s letters reveal the depth of affection in which he held his wife and the girls, his home in Morpeth, and the country and people of Northumberland. The old legend that he walked along the lanes of the county sowing acorns so that England’s navy should never want for oak trees is true: he was an early and conspicuous conservationist.

Collingwood himself returned to England in 1786 and spent the only significant period of his life ashore. A year after leaving the West Indies he received the devastating news in a touching letter from Nelson that Wilfred, his brother and fellow captain, had died of an illness. When he was not in London using his connections to try to get another ship (in peace-time there was tremendous competition for each command as much of the fleet was laid-up) he was at home in Northumberland. Such was the status of a captain in the Navy, and so impressive a man had Collingwood become after nearly 20 years at sea, that he was able to successfully court the daughter of the Mayor of Newcastle, Sarah Blackett, whom he married in 1791. They went to live in Morpeth, in the house that still bears his name on Oldgate on the banks of the River Wansbeck. They had two daughters, little Sal and Mary Patience. For the rest of his life Collingwood’s letters reveal the depth of affection in which he held his wife and the girls, his home in Morpeth, and the country and people of Northumberland. The old legend that he walked along the lanes of the county sowing acorns so that England’s navy should never want for oak trees is true: he was an early and conspicuous conservationist.

The world was changing. Britain was having to adapt to the loss of her most precious colony. The industrial revolution was transforming her domestic landscape. Collingwood’s fellow Northumbrians George Stephenson and William Hedley, still in their shorts, would become pioneers of the locomotive. Across the English Channel, a new revolution was brewing in France. Within two years the French would have executed their king and Britain would be at war. Neither Collingwood nor Nelson would survive that war.

Collingwood’s long experience as a seaman and officer were put to good use. He was a consummate professional. His ability to read the mind of the enemy and of his own men was admired by all those who knew and served with him. He was reserved in public, acutely conscious of both his provincial origins and of the isolation that a senior officer must impose on himself. He could not be friends with junior officers, nor with the men of the lower decks. Nevertheless, his compassion for their welfare and his sense of community with comrades of all ranks is unmistakeable from both his correspondence and from the testimony of those whom he commanded. He was known to weep at the end of a commission when he had to pay his ship’s company off; and there were wise heads at the Admiralty in London who knew that they could confidently send him troublemakers. Compassionate he may have been, but it was said that one of his looks of displeasure was worse than a dozen lashes at the gangway. He was not a man whose authority one would challenge.

Collingwood fought in his first great sea battle against the French in 1794 at the age of 46. He was captain on Admiral Bowyer’s flagship Barfleur, a first-rate ship-of-the-line carrying 98 guns and more than 800 men. Known as the Glorious First of June, the battle was not in truth particularly glorious. The British fleet failed to intercept a grain convoy from America heading to France and the two fleets both retired with several ships badly damaged. More insulting than the result, from Collingwood’s point of view, was that most of the captains in the British fleet received medals from the king. Collingwood, for reasons, he believed, of personal malice, did not. It was an almost unbearable professional blow in spite of the kind support he received from many colleagues, Nelson included.

Collingwood was unable to right this wrong for three years. During that time he served in the Mediterranean with Nelson under Sir John Jervis. Jervis’s 15-strong squadron, though small, was now trained to a peak of sea-going efficiency and battle readiness, on permanent blockade of the French and Spanish fleets between Cadiz and Toulon. Collingwood, in the 74-gun HMS Excellent, was perfectly in agreement with Jervis that discipline and gunnery would be the secret to beating the enemy. Collingwood at this time trained his crews to fire an extraordinary three broadsides in three and a half minutes — a rate never bettered in the age of sail. In tribute, the Royal Navy’s school of gunnery at Fareham is named HMS Collingwood.

Since 1794 the British had been developing new naval tactics at sea while the French and Spanish fleets kept safe in their harbours. Jervis, Nelson, Collingwood and other forward-thinking officers had begun to believe that the enemy must be annihilated by destroying its ships, permanently removing the threat of future fleet actions. Against a Spanish fleet of 25 ships off Cape St Vincent, at the extreme south-west corner of Portugal, they got their chance to prove their new ideas. Nelson, impetuous, attacked first but was soon in trouble and surrounded. Collingwood, blazing away, came to his rescue and destroyed four enemy ships in the process. Nelson won undying fame. Collingwood won two medals (the second to make up for the previous slight) and the admiration of his peers.

The following years were filled with hard sea-miles, endless blockade and hardship in all weathers, with only very short periods ashore and fewer at home. After the brief Peace of Amiens in 1802, at which time Collingwood became a rear admiral and saw his wife and children for the last time, the long, grinding build-up to the Trafalgar campaign saw him more or less continuously stationed off Brest, blockading the French Atlantic fleet. Collingwood’s letters during these years, alternately wistful, rhetorically anti-French, grumpy and indomitable, reveal a middle-aged man, old before his time through overwork and what these days we would call micro-management. He was indulgent to his midshipman and sailors, hard on his officers, unstinting in his duty. His only companion was his faithful dog Bounce, an almost perfect naval dog except for its dislike of gunfire. Collingwood was known to sing poor Bounce to sleep in his own cot with Shakespearean sonnets adapted to canine sensibilities. If long years of war and service had worn him to a thread, his famous wit survived intact. His put-downs were the stuff of legend and his correspondence, especially with his sisters and sisters-in-law, is full or charm and gossip. His handwriting, almost to the end, was perfect copperplate with a flourish of the tail on every ‘d’.

In the summer of 1805 Collingwood pulled off a masterstroke. Blockading the Spanish fleet in Cadiz with just four ships, he found himself one morning confronted with Admiral Villeneuve’s French battle fleet, newly arrived from the Indies having given Nelson the slip. Collingwood managed to convince the French, without firing a shot, that he had waiting just over the horizon a large number of reinforcements and, after what must have been a horribly tense few hours, shepherded them into Cadiz where they remained, cooped up, until the morning before Trafalgar: 21st October, 1805.

Nelson’s fate in that battle is famous. Collingwood’s, at the head of the lee column of battle, was to be first into the fight and last out of it, with fifty dead and many more wounded. Surviving his friend and comrade, Collingwood found himself at the age of 57 in command of the British fleet of 27 ships of the line, most of them virtually wrecks. That no British ship was lost in the hurricane that followed is an almost miraculous testament to seamanship and raw courage; that Collingwood felt forced to sink or burn all the enemy prizes (depriving the officers and men of the fleet of small fortunes) proved a decision which attracted the highest praise of his superiors and the everlasting enmity of some of his captains.

The years after Trafalgar, when the newly-created Baron Collingwood became virtual Viceroy of the Mediterranean were, as the historian Piers Mackesy put it, ‘not of battle. The fights were small, fierce encounters of sloops and gunboats, cutting-out expeditions, attacks on batteries. Only once did the enemy come out in force. Yet the scale was heroic; and over the vast canvas towers the figure of Collingwood.’ His management of delicate diplomatic relations binding fragile alliances of deys, beys, pashas, emperors, kings and queens was extraordinarily sure-footed. He prevented the French fleet from holding any part of the Mediterranean. His conduct in exploiting the Spanish anti-French uprising of May 1808 paved the way for Wellington’s ultimately successful Peninsular campaign. By the time that he died, at sea on March 7th 1810 on his way home from Menorca, he had ensured final British victory at sea against the French not by winning battles, but by preventing them.

That Collingwood gave his entire professional life for his country in the hope of eventual peace says much about the time in which he lived and even more about his personal qualities. That he never saw England or his wife and children for the last seven years of his life is a tragedy. That he has spent the last 200 years almost entirely neglected, overshadowed by the exploits of his brilliant but flawed friend Nelson, is a historical injustice which his bicentenary ought, finally, to redress.

Max Adams’s biography ‘Admiral Collingwood, Nelson’s own hero’ (Weidenfeld & Nicholson 2005) was written as a result of a Winston Churchill Fellowship enabling him to research and travel in Collingwood’s wake. A bicentenary edition of his book, ‘Collingwood, Northumberland’s Heart of Oak’ is now available from Newcastle Libraries, Tyne Bridge Publishing.

Return to TOP OF PAGE

Collingwood – Northumberland’s Heart of Oak (Audio Book)

The Collingwood 2010 Festival website is pleased and honoured to be able to provide here Max Adam’s wonderful ‘Collingwood – Northumberland’s Heart of Oak’ as an audio book, read by the author himself.

The Collingwood 2010 Festival website is pleased and honoured to be able to provide here Max Adam’s wonderful ‘Collingwood – Northumberland’s Heart of Oak’ as an audio book, read by the author himself.

The book is divided into 12 parts, each of which is started by clicking on the respective link below. Please note that an small audio player will open in a new window, from which the usual controls are accessed.

An illustrated bicentenary edition of the printed book is available from Newcastle Libraries, Tyne Bridge Publishing.

Image detail from “The Heroic Exploits of Admiral Lord Collingwood in HMS Excellent at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent’ by John Wilson Carmichael, courtesy of the Newcastle upon Tyne Trinity House.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10 Part 11 Part 12

Return to TOP OF PAGE

Cuthbert Collingwood’s Schooldays

Given that it has been in existence since the 16th century, and the important role it has played in the life of the city, the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle, has had its share of distinguished former students (known as Old Novos). Cuthbert Collingwood is one of them.

In truth, Collingwood’s time at the school was probably very brief; the co-editor of the school’s history, Brian Mains, believes it was probably as little as six months (unfortunately the school’s records for this period were lost a long time ago). By the age of 13, Collingwood was at sea. The reason for his brief stay was in all probability the same reason for his attendance in the first place.

Though from a distinguished gentry family, the Collingwoods had no money. John Scott, who as Lord Eldon was Lord Chancellor for twenty years from 1807, recalled that Collingwood and he ‘were class fellows at Newcastle. We were placed at that school because neither his father or mine could afford to place us elsewhere.’

It was a very different institution then, of course, based upon a ‘pure classical foundation’ overseen by the ‘hard but highly capable’ Head, Hugh Moises: ‘Latin was the meat course and salads and desserts were few’.

The success of Collingwood and Scott shines a light on the social and educational history of the RGS. Like similar ancient grammar schools up and down the land, the RGS produced many high-powered and successful people over the centuries. Some, coming from wealthy families, will have given the impression that future success was inevitable given the silver spoon they were born with. Collingwood and Scott may have been ‘gentle born’, but were relatively impoverished.

The RGS of the 18th century had a pretty comprehensive social intake, varying from the sons of clergymen and gentry, to the ‘middling sort’, and sons of craftsmen and even ‘menial servants’ who won their way from truly poor homes into the school and to success beyond. It was for them, above all, that the school was founded, undoubtedly in some form some decades before it was officially endowed and put on a more secure footing by Horsley’s bequest of 1545. It was modestly priced to those who could pay fees, but was free (apparently) to the poor as well as to the sons of Freemen.

For Collingwood, and his financially challenged family, the route to success in life was the Royal Navy. University required substantial funds or, for the few, a scholarship; the army needed the purchase of a commission and private funding beyond that; the law demanded capital too. The Navy offered what amounted to free entry, an education, a career structure and the lure of prize money and glory.

Perhaps we must confess that even the exciting range of extra-curricular opportunities a school like the RGS offers cannot quite match the challenge of being at sea as a midshipman, age a13, on a fully equipped frigate! One wonders what a modern regulatory framework would have made of the dangers and ferocious discipline of such a life, however.

A school such as the RGS is proud of its distinguished Old Novos, ranging from politicians to musicians, architects to academics. To have as one of them a genuine local hero, and one of the great sailors of a nation and region with a great maritime history, is naturally a source of great pride. Collingwood left an indelible mark on European history as admiral, politician and diplomat, playing a pivotal role in saving Europe from Napoleonic domination; many more played perhaps less distinguished, but no less heroic, roles in the defence of freedom in the two world wars.

The school is delighted to be involved in the bi-centennial celebrations. Collingwood maybe have only been with us a short time, though his affection for the area remained intact all his life. Upon news of his death the Newcastle Courant praised a ‘highly distinguished and gallant townsman’, whose ‘services will forever be in the memory of a grateful country’. Those words his old school can happily echo.

Simon Tilbrook, Head of History,

Royal Grammar School, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Return to TOP OF PAGE

Collingwood at Trafalgar

Collingwood, as Nelson’s second-in-command, led one of the two columns that struck the line of the Franco-Spanish Combined Fleet shortly after midday on 21 October 1805. The aim was to engage and defeat the enemy rear while Nelson went for the enemy fleet flagship and his squadron occupied the attention of the Combined Fleet’s van and centre. Collingwood’s flagship was the first to be engaged as HMS Royal Sovereign, with a new copper bottom, was fast and pulled ahead of the ships following. She aimed to cut in between the Spanish Santa Anna, flagship of the rearward enemy squadron, and the French Fougeux.

The latter ships tried to shut Royal Sovereign out but Collingwood was not to be denied and ordered Royal Sovereign to sail straight at Fougueux’sbowsprit forcing the latter to turn to starboard, and allowing a raking shot along the full length of the Spanish flagship before loosing a broadside against the Frenchman to starboard. Great damage was done to both ships and their crews but both continued to fight. Four more enemy warships joined in before being diverted by other threats as the rest of the fleet came up. Royal Sovereign’s yardarms became entangled with those of theSanta Anna as the great three deckers poured shot into each other.

Through the inferno Collingwood remained apparently unperturbed, pacing up and down, eating an apple, even as the flagship’s master was killed by a cannon ball beside him and Collingwood suffered very bad bruising in the leg from a flying splinter of wood as well as being hurt in the back by a ball passing by literally too close for comfort. In a world of inaccurate smooth bore weapons injury or death was a matter of chance. The odds favoured the British second-in-command that day, not the fleet commander.

Although the Spanish in Santa Anna fought well that day killing forty seven men of Royal Sovereign’s complement and wounding twice as many, the Spanish ship lost almost as many men again as superior British rates of fire told their usual terrible story.

As her fire slackened it looked as if Santa Anna had surrendered but she made a last attempt to get away moving ahead of Royal Sovereign and raking her before being re-engaged by the British ship’s starboard guns. Then two of Santa Anna’s weakened masts fell and she finally struck her colours at 2.20. As she did so Royal Sovereign lost her mainmast also.

Now a boat arrived from HMS Victory. Lieutenant Alexander Hills came on board to inform the second-in-command that Nelson had been wounded. Collingwood sensed from Hills’ expression that the situation was very serious. He now ordered the frigate Euryalus to take Royal Sovereign in tow and the frigate’s distinguished Captain Blackwood was sent on board Santa Anna to bring its admiral, Alava, on board. The latter had been seriously wounded in the head and sent his flag captain with his sword. Collingwood sent the captain back to look after his admiral.

As the ships that had originally led the enemy fleet came round to attempt to rescue the centre and rear, Collingwood drove them away, engaging them under tow until enemy fire broke the cable, while ordering the aftermost ships in his squadron to see them off. Blackwood now closed Victoryto hear the news of Nelson’s death. He then took Captain Hardy to meet Collingwood and surrender Nelson’s command to him.

Hardy told Collingwood that Nelson had ordered the fleet and its captures to go to anchor but Collingwood disagreed. Instead, shifting his flag toEuryalus which again took Royal Sovereign in tow, he ordered his ships to make towards Gibraltar, disabled ships to be towed. Now Collingwood’s luck finally ran out. Worsening weather caused Euryalus and Royal Sovereign to collide and Collingwood belatedly ordered the crippled fleet to anchor. The storm struck in full force on the 22nd and lasted on and off for four days. In the terrible conditions Collingwood set about destroying the prizes, some of which also sank, made their escape or were recaptured (among them the Santa Anna), leaving only four out of the original seventeen captured ships in British hands. Collingwood’s decision-making caused controversy both at the time and since.

Nevertheless Collingwood remained sufficiently trusted by the Admiralty and the British Government as a whole to remain to be worked to death over the next four and a half years as C-in-C of the Mediterranean Fleet. His central involvement in the overall destruction of the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar overshadowed his losses in the storm and he emerged from the battle as Baron Collingwood, its other, but still living hero.

Eric Grove became a civilian lecturer at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in 1971 and left at the end of 1984 as Deputy Head of Strategic Studies. He later taught at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich. From 1993-2005 he was at the University of Hull becoming Reader in Politics and International Studies and Director of the Centre for Security Studies. In 2005 Dr Grove moved to the University of Salford where he is now Professor of Naval History. A prolific author who frequently appears on radio and television, he is a Vice President of the Society for Nautical Research, a Member of Council of the Royal Navy Records Society and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

Return to TOP OF PAGE

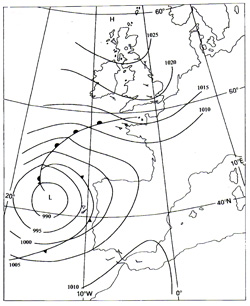

21st October 1805, 0800 hours: and now, the Shipping Forecast…

At frequent intervals since 1805, the argument as to whether Collingwood made the right choice after the Battle of Trafalgar is re-run. This of course relates to his decision to deliberately sacrifice a number of prizes and for the fleet to run for Gibraltar in the midst of a gale.

Those who support the Admiral’s position point to aspects of basic seamanship: the principle of not anchoring on a lee shore in the face of a coming storm and the realised or likely inablility of many of the ships, severely damaged in battle, to anchor anyway. Those who decry his decision point to the loss of the ships (and their crews) and the significant negative impact that had on the levels of much-needed prize money awarded to the survivors. They also point to Nelson’s words, uttered shortly before his death, in which he is reported to have issued instructions for the fleet to anchor which if true and known to Collingwood, he chose to disregard.

As part of the 2010 programme of the North-East Branch of the Nautical Institute and integrated into the calendar of the Collingwood 2010 Festival, Dr. Dennis Wheeler, an expert on the weather of Trafalgar from the University of Sunderland, made a fascinating presentation on the Great Storm and the meteorological information that would have been available to Collingwood, his officers and indeed those on the Spanish and French ships, Dr. Wheeler speaks from a position of considerable knowledge and expertise, having studied the meteorological entries in the log books of thousands of ships, particularly those of naval vessels, as part of the CLIWOC (Climatological data for the World’s Oceans 1750 – 1850) Project.

It was indeed interested to learn how detailed the information was and how close it was to the equivalent data recorded today. Indeed, the point was made that the average seamen in 1805 was a sight more “tuned-in” to the weather than his modern counterpart, technology aside.

From the available information, drawn from English and Spanish ships, as well as the observations of a number of shore stations, significantly including the Real Observatorio de la Armada, Cadiz, Dr. Wheeler has compiled a detailed weather picture for the 21st October 1805. The day dawn calm and it is well known that from the first sightings at daybreak, it took until midday for the two fleets to close. During the battle, the weather began to turn and it is said that the mortally wounded Nelson, lying on the orlop deck of HMS Victory, felt the increased movement of the ship in the rising swell, prompting his concerns.

Dr. Wheeler is entirely confident that Collingwood would have seen the changing weather and correctly assessed the severity of the coming gale, estimated the time the sea and wind conditions would take to worsen and would have fully realised the impact that the storm might have on the fate of the ships. This despite all the other management decisions required of him in the aftermath of that huge sea battle. Indeed, his order to get as far off the coast as possible before it became necessary to reduce sail might be seen as an entirely sound decision based on pure seamanship and possibly one of the easier decisions to make.

What neither he, nor anyone else, would (and could) have realised was the duration of the coming gale, as there was no long-range information from out in the Atlantic ocean available, such as would be provided by satellite images today. On the basis of his experience and knowledge of those waters at that time of year, he would most likely have believed that it would last around 48 hours at the most. He would therefore have considered that the majority of the ships were capable of riding it out, given sufficient distance off the shore to begin with. In fact, it lasted for the best part of a week and was truly the meteorological event of the first half of the century in north-east European waters.

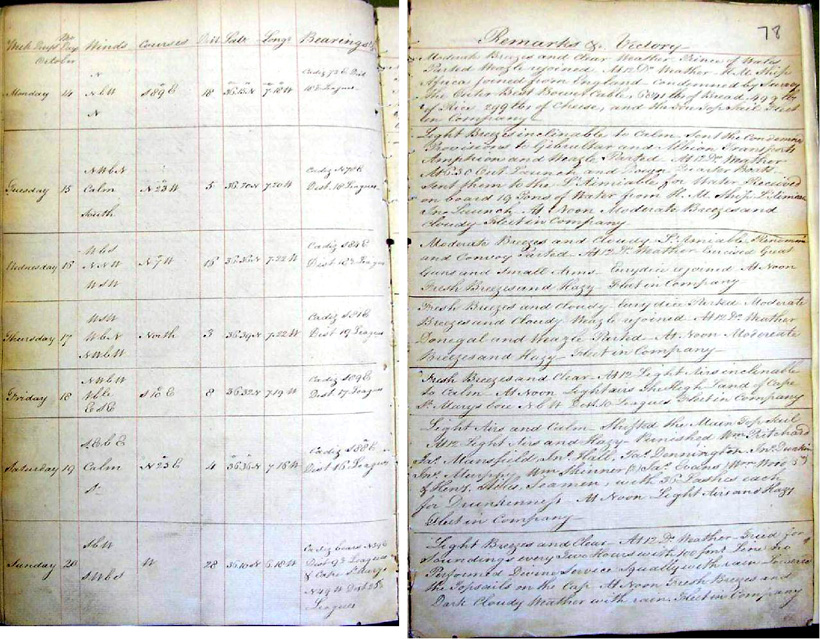

To the great interest and slight amusement of many in the audience, Dr. Wheeler produced as part of his presentation what would have been the Shipping Forecast for the morning of 21st October, along with the weather map for the region. With his kind permission they are reproduced below, along with an extract from the logbook of HMS Victory, written by Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy.

In conclusion, it was demonstrated that Collingwood remained entirely focused on the mission, drawing on the following extract from his despatch to the Admiralty, written immediately after the battle: “The storm, being so violent, and many of our ships in most perilous situations, I found it necessary to order the captures, all without masts, some without rudders, and many half full of water, to be destroyed, except such as were in better plight; for my object was their ruin and not what might be made of them.”

THERE ARE WARNINGS OF GALES IN PORTLAND, PLYMOUTH, BISCAY, FITZROY, TRAFALGAR AND SOLE

THERE ARE WARNINGS OF GALES IN PORTLAND, PLYMOUTH, BISCAY, FITZROY, TRAFALGAR AND SOLE

THE GENERAL SYNOPSIS AT 0800

LOW TRAFALGAR 985 MOVING SLOWLY SOUTH EASTWARDS DEEPENING 980 BY SAME TIME TOMORROW HIGH FAIR ISLE 1030

THE AREA FORECASTS FOR THE NEXT 24 HOURS

VIKING NORTH UTSIRE SOUTH UTSIRE FORTIES

N OR NE 3 OR 4. MODERATE

CROMARTY FORTH TYNE

N OR NE 2 OR 3. MODERATE

DOGGER FISHER GERMAN BIGHT HUMBER

NE 3 OR 4. MODERATE

THAMES DOVER WIGHT

NE 4 OR 5 INCREASING 6 OR 7 LATER. MODERATE OR GOOD

PORTLAND PLYMOUTH

E 5 OR 6 INCREASING 7 GALE 8 LATER. RAIN OR SHOWERS MODERATE OR POOR

BISCAY

E OR SE 4 INCREASING 6 OR 7. MODERATE OR GOOD

FITZROY SOLE

E OR SE 5 OR 6 NE IN WEST FITZROY INCREASING 7 GALE 8 LATER. RAIN MODERATE

TRAFALGAR

SW 1 OR 2 INCREASING 5 OR 6 VEERING WEST BECOMING GALE FORCE 8 LATER. GOOD BECOMING MODERATE OR POOR RAIN LATER

LUNDY FASTNET IRISH SEA SHANNON

E OR SE 4 OR 5 INCREASING 6. MODERATE

IRISH SEA MALIN ROCKALL

SE 2 OR 3. MODERATE

BAILEY FAROES SOUTH EAST ICELAND

VARIABLE 1 OR 2. MODERATE OCCASIONALLY POOR

Extract from the logbook of HMS Victory for 21st October 1805, including observations of wind force and direction, as well as narrative entries on the changing conditions “Light winds and squally with rain. At 2 taken aback…” and “…at 8 light breezes and cloudy.”

Return to TOP OF PAGE

Lord Collingwood’s links with Menorca.

One of Menorca’s foremost groups, the Asociación Menorca Britannia actively encourages and promotes a better understanding of the historic and cultural links between the Menorquin people and the British community. Since 1708 and the arrival of the British during the reign of Queen Anne, subsequently to become a British Crown Colony on the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, there has been a unique and deep rooted British influence (and mutual friendship) which can be clearly seen by today’s visitors. Although Great Britain voluntarily handed Menorca back to the Spanish crown at the Treaty of Amiens in 1802 that friendship continues to the present day.

Cuthbert Collingwood’s outstanding career is known to most with an interest in naval history and is only overshadowed, perhaps mistakenly, by that of his great friend Admiral Lord Nelson. It was after the unfortunate and premature death of Nelson early during the Battle of Trafalgar that the true courage, humanity and dedication to his country were shown by the great man celebrated by this Festival. Collingwood showed his great humanity during the storm that followed by sending out boats to rescue hundreds of Spanish and French seamen from stricken or sinking ships. He arranged the safe landing of these “prisoners” in Cadiz and into the hands of the Governor of Andalucia, the Condé de Solana. A friendship was cemented with the gift of barrels of wine being sent to the British ships. Reportedly in return, a return gift of a keg of British beer and some cheddar cheese was given by Collingwood. Many letters between the two men display their mutual respect and friendship thereafter.

Following the Battle of Trafalgar Collingwood expected to retire after a lifetime at sea, however this wasn’t to be. The Admiralty being short of senior commanders refused his letter of resignation and ordered him to Port Mahón, Menorca to take charge of the British Mediterranean Fleet. Britain and Spain having an agreement to jointly use the port facilities of the world’s second largest, deep water natural harbour. As always his King and Country again came first.

During the last five years of his life Collingwood dutifully carried out his orders, his fleet blockading the French south coast ports, patrolling the Gulf of Leon and assisting the Spanish in defending their mainland coastline and the Balearic Islands.

As his shore base, Collingwood took residence in a splendid colonial style house “Fonduco” overlooking the harbour above where his flag ship was anchored. This is now a charming privately run hotel retaining all the features and alterations carried out during his time here

It was in the year prior to his death and during the Napoleonic War that Collingwood ordered an escort of frigates to a merchant ship bringing to Menorca one of the world’s largest organs ever manufactured. This was installed in the parish church of Sta. Maria in Mahón. With over 3,000 pipes and four keyboards the organ is played every day and is just part of the heritage left by Lord Collingwood on Menorca. This world famous organ is also celebrating it’s 200th. Anniversary this year, 2010.

During his last year Collingwood was ailing and in pain spending many periods bedridden – it is now believed that he was suffering from stomach cancer – but he stoically “soldiered on” until being obviously very ill and dying he was carried to his ship to make his way to England. Unfortunately he died on board still within Menorcan waters.

The Asociación Menorca Britannia, in cooperation with the Island Government, proudly honoured the memory of Lord Collingwood at the end of March 2010, completing the full circle, so to speak, from his place of birth to his last post and eventual place of death.

Return to TOP OF PAGE

A Tribute in Song:

Tyneside folk singer and song writer Pete Wood has composed a song in honour of Admiral Lord Collingwood. The work was first performed in public on the evening of 7th March 2010, 200 years to the day since Collingwood’s death. It is entitled “Cuddy”, that being the affectionate nickname given to him by his crews. Pete has kindy agreed to the lyrics of the song being reproduced here.

CUDDY

He was born in Newcastle-on-Tyne

Soon sailed on a ship of the line

With Roddam and Braithwaite he learnt his trade

Northumbrians all they were made

Preston and Portland his ships in the west

Fighting the French and the rest,

He was made lieutenant at Bunker Hill

And Geordies remember him still

Chorus

Cuddy’s the boy for me

Yes Cuddy’s the man at sea

Fighting the French where’er they be

Cuddy’s the boy for me

At the glorious first of June

Barfleur had sails in full tune

Flag Captain Collingwood fought with renown

But Bowyer and Howe took the crown

At St Vincent the Spanish came on

He took two of their ships in the van

He dismasted the greatest vessel they had

Santissima Trinidad

Whilst Nelson went chasing the French east and west

Cuthbert kept watch on the rest

Keeping the Spanish from putting to sea

For month after month on his lee.

The enemy fleets they made way

Two columns were formed on that day

The weather with Nelson in Vict-or-ee

But Collingwood led with the lee

So swift was the brave Collingwood

That he was the first to taste blood

The Sovereign fired the very first shot,

And withstood the Spanish onslaught

Then after Nelson was gone,

Cuddy the battle had won

The prizes were lost, as the storm did rage

But he saved the fleet of the age

After Trafalgar he ailed

Ne’er again to England he sailed

They made him a Lord and a medal of gold

But “We need you at sea” he was told

Yes was a son of the Tyne

Sailed many’s the ship of the line

Was buried with Nelson his friend of renown

But for Geordies he takes the crown

© Pete Wood 2010. www.petewood.co.uk

Return to TOP OF PAGE

The Great Man’s Own Words: quotes from Collingwood himself

It is not unusual to hear some of Collingwood’s speeches described as ‘Churchillian’ in character, but one must remember who came first. Rather, should it not be that some of Churchill’s speeches could have drawn inspiration from the words of Collingwood? Just like Churchill however, Collingwood could be dry and cutting when he rounded on a particular individual. Yet his writings also display an undoubted affection and beautifully capture the significance of the English countryside to a man who was, over a forty-four year seagoing career, to see little of it. Like many a man too, Collingwood developed a close bond with his dog – the almost equally famous ‘Bounce’ – and many readers will instantly recognise his muses and observations on his canine companion. Ultimately however, Collingwood will perhaps be best known for the series of despatches sent to their Lordships at the Admiralty in the days immediately after the Battle of Trafalgar, when his words not only reported both a victory over the enemy and the loss of Nelson, but managed at the same time to convey sentiments from the very bottom of his own heart and those that would be echoed by the nation. Here then, is but a brief selection….

“My dog is a good dog, delights in the ship and swims after me when I go in the boat.”

Collingwood to his sister Mary (July 1790), Hughes 11, Sheerness.

“I am sure I have great cause for thankfulness for such a family, a wife that is goodness itself, and two healthy children that with her care and her example can scarce fail to be like her. All my troubles here seem light when I look Northward and consider how well I am rewarded for them.”

Collingwood to Sir Edward Blackett (December 1793) Hughes 20, from HMS Prince at Spithead.

“I hope to find Sall can swim like a frog, the darling. Why should a miss be more subject to drown by an accident than a master?”

Collingwood to Dr Carlyle (July 1795) Hughes 34, from HMS Excellent

“I have no desire to command in a port, except at Morpeth, where I am only second.”

Collingwood to Dr Alexander Carlyle (April 1799) Hughes 48, Morpeth.

“Then I will plant my cabbages again, and prune my goosberry trees, cultivate roses, and twist the woodbine through the hawthorn hedge…”

(1800).

“A good tempered man, full of vanity, a great deal of pomp, and a pretty smattering of ignorance – nothing of the natural ability that raises men without the advantages of learned education”

On Sir Hyde Parker, to his sister (November 1800) Hughes 62 from HMS Barfleur.

“I should be much obliged to you if you would send Scott a guinea for me, for these hard times must pinch the poor old man, and he will miss my wife, who was very kind to him.”

To his father -in-law, regarding his gardener at Morpeth (1801).

“Lord Nelson is an incomparable man, a blessing to any country that is engaged in such a war. His successes in most of his undertakings are the best proofs of his genius and his talents. Without much previous preparation or plan he has the faculty of discovering advantages as they arise, and the good judgement to turn them to his use. An enemy that commits a false step in his view is ruined, and it comes on him with an impetuosity that allows him no time to recover.”

Collingwood to Dr Alexander Carlyle (August 1801) Hughes 69, from HMS Barfleur

“I should recommend Northumberland for your residence, a fine healthy air; in winter a comfortable fire and friends about you that would be made happy by your neighbourhood.”

Collingwood to Mrs Stead (May 1802) Hughes 75, Thorpe Lee

“I have got a nurseryman man here from Wrighton [Ryton]. It is a great pity that they should press such a man because when he was young he went to sea for a short time. They have broken up his good business at home, distressed his family, and sent him here, where he is of little or no service. I grieve for him poor man.”

Collingwood to John Erasmus Blackett (July 1804) GLNC 96, from HMS Culloden off Ushant

“Captain, I have been thinking, whilst I looked at you, how strange it is that a man should grow so big and know so little. That’s all, Sir; that’s all.”

On Captain Rotheram: attributed to Collingwood in ‘Sea Drift’ (1858).

“AM. Departed this life Mr. Samuel Price 3rd lieutenant, who for his gentleness of disposition, equanimity, vigilance and unwearied attention to the Service, was universally regretted. Every action of his life was guided by justice, candour and honour; the years of a youth were enriched with knowledge equal to long experience; he discharged his duty to his country like an officer, and to all mankind as their friend; no wonder he lived beloved, and died lamented.”

Collingwood, Log (June 6th 1773) Princess Amelia, Port Royal

“Now, gentlemen, let us do something today which the world may talk of hereafter.”

To his Officers before the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 Oct 1805. Anectdotal remark, probably reported to the biographer Newnham-Collingwood by William Conway, the Admiral’s secretary. Newnham-Collingwood (1837) i, 174

“What would Nelson give to be here?”

At the start of the Battle of Trafalgar, as HMS Royal Sovereign surged towards the Spanish line, well ahead of any other British ship

“Sir,

The ever-to-be lamented death of Vice-Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson, who, in the late conflict with the enemy, fell in the hour of victory, leaves to me the duty of informing my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, that on the 19th instant, it was communicated to the Commander in Chief, from the ships watching the motions of the enemy in Cadiz, that the Combined Fleet had put to sea; as they sailed with light winds westerly, his Lordship concluded their destination was the Mediterranean, and immediately made all sail for the Streights’ entrance, with the British Squadron, consisting of twenty-seven ships, three of them sixtyfours, where his Lordship was informed, by Captain Blackwood (whose vigilance in watching, and giving notice of the enemy’s movements, has been highly meritorious), that they had not yet passed the Streights.

On Monday the 21st instant, at day-light, when Cape Trafalgar bore E. by S. about seven leagues, the enemy was discovered six or seven miles to the Eastward, the wind about West, and very light; the Commander in Chief immediately made the signal for the fleet to bear up in two columns, as they are formed in order of sailing; a mode of attack his Lordship had previously directed, to avoid the inconvenience and delay in forming a line of battle in the usual manner. The enemy’s line consisted of thirty-three ships (of which eighteen were French, and fifteen Spanish), commanded in Chief by Admiral Villeneuve: the Spaniards, under the direction of Gravina, wore, with their heads to the Northward, and formed their line of battle with great closeness and correctness; but as the mode of attack was unusual, so the structure of their line was new; it formed a crescent, convexing to leeward, so that, in leading down to their centre, I had both their van and rear abaft the beam; before the fire opened, every alternate ship was about a cable’s length to windward of her second a-head and a-stern, forming a kind of double line, and appeared, when on their beam, to leave a very little interval between them; and this without crowding their ships. Admiral Villeneuve was in the Bucentaure, in the centre, and the Prince of Asturias bore Gravina’s flag in the rear, but the French and Spanish ships were mixed without any apparent regard to order of national squadron.

As the mode of our attack had been previously determined on, and communicated to the Flag-Officers, and Captains, few signals were necessary, and none were made, except to direct close order as the line bore down.

The Commander in Chief, in the Victory, led the weather column, and the Royal Sovereign, which bore my flag, the lee.

The action began at twelve o’clock, by the leading ships breaking through the enemy’s line, the Commander in Chief about the tenth ship from the van, the Second in Command about the twelfth from the rear, leaving the van of the enemy unoccupied; the succeeding ships breaking through in all parts, astern of the leaders, and engaging the enemy at the muzzles of their guns; the conflict was severe; the enemy’s ships were fought with a gallantry highly honourable to their Officers; but the attack on them was irresistible, and it pleased the Almighty Disposer of all events to grant his Majesty’s arms a complete and glorious victory. About three P.M. many of the enemy’s ships having struck their colours, their line gave way; Admiral Gravina, with ten ships joining their frigates to leeward, stood towards Cadiz. The five headmost ships in their van tacked, and standing to the Southward, to windward of the British line, were engaged, and the sternmost of them taken; the others went off, leaving to his Majesty’s squadron nineteen ships of the line (of which two are first rates, the Santissima Trinidad and the Santa Anna,) with three Flag Officers, viz. Admiral Villeneuve, the Commander in Chief; Don Ignatio Maria D’Aliva, Vice Admiral; and the Spanish Rear-Admiral, Don Baltazar Hidalgo Cianeros.

After such a Victory it may appear unnecessary to enter into Encomiums on the particular Parts taken by several Commanders; the Conclusion says more on the Subject than I have Language to express; the Spirit which animated all was the same; when all exert themselves zealously in their Country’s Service, all deserve that their high Merits should stand recorded; and never was high Merit more conspicuous than in the Battle I have described.

The Achille (a French 74), after having surrendered, by some Mismanagement of the Frenchmen took Fire and blew up; Two hundred of her Men were saved by the Tenders.

A Circumstance occurred during the Action, which so strongly marks the invincible Spirit of British Seamen, when engaging the Enemies of their Country, that I cannot resist the Pleasure I have in making it known to their Lordships; the Temeraire was boarded by Accident, or Design, by a French Ship on one Side, and a Spaniard on the other; the Contest was vigorous, but in the End, the combined Ensigns were torn from the Poop, and the British hoisted in their Places.

Such a Battle could not be fought without sustaining a great Loss of Men. I have not only to lament, in common with the British Navy, and the British Nation, in the Fall of the Commander in Chief, the Loss of a Hero, whose Name will be immortal, and his Memory ever dear to his Country; but my Heart is rent with the most poignant Grief for the Death of a Friend, to whom, by many Years’ Intimacy, and a perfect Knowledge of the Virtues of his Mind, which inspired Ideas superior to the common Race of Men, I was bound by the strongest Ties of Affection; a Grief to which even the glorious Occasion in which he fell, does not bring the Consolation which perhaps it ought; his Lordship received a Musket Ball in his Left Breast, about the Middle of the Action, and sent an Officer to me immediately with his last Farewell; and soon after expired.

I have also to lament the Loss of those excellent Officers Captains Duff of the Mars, and Cooke of the Bellerophon; I have yet heard of none others.

I fear the Numbers that have fallen will be found very great when the Returns come to me; but it having blown a Gale of Wind ever since the Action, I have not yet had it in my Power to collect any Reports from the Ships.

The Royal Sovereign having lost her Masts, except the tottering Foremast, I called the Euryalus to me, while the Action continued, which Ship lying within Hail, made my Signals, a Service Captain Blackwood, performed with great Attention. After the Action, I shifted my Flag to her, that I might more easily communicate my Orders to, and collect the Ships, and towed the Royal Sovereign out to Seaward. The whole Fleet were now in a very perilous Situation, many dismasted; all shattered in Thirteen Fathom Water, off the Shoals of Trafalgar; and when I made the Signal to prepare to anchor, few of the Ships had an Anchor to let go, their Cables being shot; but the same good Providence which aided us through such a Day preserved us in the Night, by the Wind shifting a few Points, and drifting the Ships off the Land, except Four of the captured dismasted Ships, which are now at Anchor off Trafalgar, and I hope will ride safe until those Gales are over.

Having thus detailed the Proceedings of the Fleet on this Occasion, I beg to congratulate their Lordships on a Victory which, I hope, will add a Ray to the Glory of His Majesty’s Crown, and be attended with public Benefit to our Country.

I am, &c.”

Collingwood’s ‘Trafalgar Dispatch’ as written on board and sent from HMS Euryalus, off Cape Trafalgar, Oct. 22, 1805. Later reproduced in a LONDON GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY.

“Sir,

In my letter of the 22d, I detailed to you, for the information of my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, the proceedings of his Majesty’s squadron on the day of the action, and that preceding it, since which I have had a continued series of misfortunes; but they are of a kind that human prudence could not possibly provide against, or my skill prevent.

On the 22d, in the morning, a strong southerly wind blew, with squally weather, which, however, did not prevent the activity of the Officers and Seamen of such ships as were manageable, from getting hold of many of the prizes (thirteen or fourteen), and towing them off to the Westward, where I ordered them to rendezvous round the Royal Sovereign, in tow by the Neptune: but on the 23d the gale increased, and the sea ran so high that many of the, broke the tow-rope, and drifted far to leeward before they were got hold of again; and some of them, taking advantage in the dark and boisterous night, got before the wind, and have perhaps, drifted upon the shore and sunk; on the afternoon of that day the remnant of the Combined Fleet, ten sail of the ships, who had not been much engaged, stood up to leeward of my shattered and straggled charge, as if meaning to attack them, which obliged me to collect a force out of the least injured ships, and form to leeward for their defence; all this retarded the progress of the hulks, and the bad weather continuing, determined me to destroy all the leewardmost that could be cleared of the men considering that keeping possession of the ships was a matter of little consequence, compared with the chance of their falling again into the hands of the enemy; but even this was an arduous task in the high sea which was running. I hope, however, it has been accomplished to a considerable extent; I entrusted it to skilful Officers, who would spare no pains to execute what was possible. The Captains of the Prince and Neptune cleared the Trinidad and sunk her. Captains Hope, Bayntun, and Malcolm, who joined the fleet this moment from Gibraltar, had the charge of destroying four others. The Redoubtable sunk astern of the Swiftsure while in tow. The Santa Anna, I have no doubt, is sunk, as her side was almost entirely beat in; and such is the scattered condition of the whole of them, that unless the weather moderates I doubt whether I shall be able to carry a ship of them into port. I hope their Lordships will approve of what I (having only in consideration the destruction of the enemy’s fleet) have thought a measure of absolute necessity.

I have taken Admiral Villeneuve into this ship; Vice-Admiral Don Aliva is dead. Whenever the temper of the weather will permit, and I can spare a frigate (for there were only four in the action with the fleet, Euryalus, Sirius, Phœbe, and Naiad; the Melpomene joined the 22d, and the Eurydice andScout the 23d,) I shall collect the other flag officers, and send them to England, with their flags, if they do not all go to the bottom), to be laid at his Majesty’s feet.

There were four thousand troops embarked, under the command of General Contamin, who was taken with Admiral Villeneuse in the Bucentaure.”

A further dispatch to the Admiralty, sent from HMS Euryalus, off Cadiz, Oct 24 1805.

“My Dear Sister – We fought a battle on the 21st and obtained a victory such as perhaps there is no instance of. We were 27 ships, the combined fleet 33. My dear friend Nelson fell in [the] middle of the battle. I followed up what he had begun…”

Collingwood to his sister (October 1805) Hughes 93, off Cadiz

“I hope I shall keep my health, but I am much worried in spirit and worn in body, and lest I should fail at an important moment I have wrote to the Admiralty to request their Lordships will allow me to come home to England and recover my shaken body, which I think you will be glad to hear. If I can but have one little finishing touch at the Frenchmen before I come it will be a glorious termination.”

Collingwood to his sister (August 1808) Hughes 162, from HMS Ocean.

“Should we decide to change the place of our dwelling…I should be forever regretting those beautiful views which are nowhere to be exceeded…The fact is, whenever I think how I am to be happy again, my thoughts carry me back to Morpeth, where, out of the fuss and parade of the world, surrounded by those I loved most dearly and who loved me, I enjoyed as much happiness as my nature is capable of.”

On his home, 1806.

“Fourteen or sixteen hours of every day I am employed. I have about eighty ships of war under my orders, and the direction of naval affairs from Constantinople to Cadiz, with an active and powerful enemy, always threatening, and though he seldom moves, keeps us constantly on the alert.”

Collingwood to Mrs Stead (April 1809) Hughes 174, from HMS Ville de Paris.

“You will be sorry to hear my poor dog Bounce is dead. I am afraid he fell overboard in the night. He is a great loss to me. I have few comforts, but he was one, for he loved me. Everybody sorrows for him. He was wiser than [many] who hold their heads higher and was grateful [to those] who were kind to him.”

Collingwood to his sister (August 1809) Hughes 184, from HMS Ville de Paris off Toulon.

“The women [under siege at Gerona] are dressed in the habits of men, are armed with muskets and behave with the greatest gallantry. The soul of a woman is the excellence of creation, but how they would spoil it by foolish fashion, affecting a timidity which they do not feel. I wish my girls were taught their exercise and to be good shots. I think it will be useful to them before long. I am sure Sarah would be a sharp shooter, a credit to any Light Corps.”

Collingwood to Mrs Stead (October 1809) Hughes 190, from HMS Ville de Paris off Barcelona.

Return to TOP OF PAGE

And Others on Collingwood

“Your judgement on these points, and zeal for the Service, promise everything that can be expected, and no one more highly estimates both, than he who has the honour to be, Sir etc, Nelson and Bronte.”

Nelson to Collingwood (July 1805), Nicholas V:57.

“I found him already up and dressing. He asked if I had seen the French fleet; and on replying that I had not, he told me to look out at them, adding that in a very short time, we should see a great deal more of them. I then observed a great cloud of ships to leeward; but could not help looking with still greater interest at the Admiral, who, during all this time, was shaving himself with a composure that quite astonished me.”

Collingwood’s servant Smith, on the morning of 21st October 1805.

“See how that noble fellow Collingwood takes his ship into action. Oh, how I envy him!”

Nelson, at the start of the Battle of Trafalgar, 21st October 1805. (Also inscribed on the Collingwood Monument, Tynemouth)

“I saw his tears with my own eyes, when the boat hailed and said my lord was dead.”

Sam, a seaman on board HMS Royal Sovereign at Trafalgar, October 1805.

“During upwards of the three years and a half that I was in this ship, I do not remember more than four or five men being punished at the gangway, and then so slightly that it scarcely deserved the name, for the Captain was a very humane man, and although he made great allowances for the uncontrolled eccentricities of the seamen, yet he looked after the midshipmen of his ship with the eye of one who felt it a duty to keep youth in constant employment…”

Baron Jeffrey de Raigersfeld, The life of a Sea Officer (published 1830).

“The Captain, a well read man as well as a clever seaman, took it into his head one day that he would like to see the midshipmen work their day’s-work from their own observations before him on the quarter deck; they did so, but only three or four out of twelve or thirteen could accomplish this with any degree of exactitude, so calling those to him who were deficient, he observed to them how remiss they were, and suddenly, imputing their remissness to their pigtails, he took his penknife out of his pocket and cut off their pigtails close to their heads above the tie, then presenting them to their owners, desired they would put them into their pockets and keep them until such time as they could work a day’s-work, when they might wear them again if they thought proper.”

Baron Jeffrey de Raigersfeld, The life of a Sea Officer (published 1830).

“A better seaman – a better friend to seamen – a greater lover and more zealous defender of his country’s rights and honour, never trod a quarterdeck. He and his favourite dog Bounce were known to every member of the crew. How attentive he was to the health and comfort and happiness of his crew! A man who could not be happy under him, could have been happy nowhere.”

Landsman Hay, Memoirs of Robert Hay (published 1953).

“…I went to the masthead, and when the Captain came on deck, which he generally did at half-past seven, he very soon spied me out … and beckoned me to come down, when he put questions to me, how such and such ropes led at the mast head, their size as to others, and bade me point them out to him upon deck by taking hold of them; if I was not quick and expert in my answers I was sent again to the mast head, and desired in a quarter of an hour to come to him in the cabin, where, being at breakfast, sometimes he made me sit down and eat, but if I answered his questions well at first, I was not ordered to the mast head a second time, but was asked to breakfast at once.”

Baron Jeffrey de Raigersfeld, The life of a Sea Officer (published 1830).

“…at last discovered him with his gardener, Old Scott, to whom he was much attached, in the bottom of a deep trench, which they were busily occupied in digging.”

A fellow Admiral, who had called on Collingwood and been directed to the garden, where he failed to locate him for some time: Newnham-Collingwood 91 (published 1828).

“I think, since heaven made gentlemen, there is no record of a better (sometimes quoted as finer) one.”

William Makepeace Thackeray.

“I met Lord Collingwood in the Strand: he was a school-fellow of mine under Moises. I had not seen him in many years – he had been so long on board Ship that he walked with difficulty – we shook hands – I observed that tears flowed down his cheeks – I asked him what so affected him – He said that a few days before, his ship’s company were paid off – that he had lost his children – all his family – that they were dear to him, and he could not refrain from what I had noticed.”

Lord Eldon’s anecdote book (1824-7).

…”on the 6th the wind came round to the westward, and at sunset the ship succeeded in clearing the harbour, and made sail for England. When Lord Collingwood was informed that he was again at sea, he rallied for a time his exhausted strength, and said to those around him, ‘Then I may yet live to meet the French once more.’ On the morning of 7th there was a considerable swell, and his friend captain Thomas, on enterng his cabin, observed that he feared the motion of the vessel disturbed him. ‘No Thomas,’ he replied, ‘I am now in a state in which nothing in this world can disturb me more. I am dying; and I am sure it must be consolatory to you, and all who love me, to see how comfortably I am coming to my end.”

Newnham-Collingwood 1837: ii, 427

“A mail from Gibraltar and Cadiz arrived on Tuesday; it has brought intelligence which will be received with the deepest concern, viz. the death of our highly distinguished and gallant townsman, Admiral Lord Collingwood. His health had long been in a declining state, but he persisted in keeping the sea, being anxious to bring the Toulon fleet to action, and by the defeat of the last naval force of the enemy, to complete the destruction of the French navy. He had not above once set his foot on shore since the great battle of Trafalgar. At length his health declined so much that he was under the necessity of determining to return to England. It pleased heaven, however, that he should see his native land no more. On the 6th ult. he left Minorca, on board the Ville de Paris, and on the 7th he breathed his last. The Ville de Paris brought his honoured remains to Gibraltar; and on Monday they arrived at Portsmouth on board the Nereus frigate. His Lordship died of a stoppage of the Pylorus, or inferior aperture of the stomach. For some time before his death he was incapable of taking any sustenance whatever. Leaving only two daughters, the title dies with His Lordship; but his services will forever live in the memory of a grateful country.”

Newcastle Courant, Sat April 21st 1810.

Return to TOP OF PAGE