(A talk to the Collingwood Society by Commodore Gary Doyle, RN, Naval Regional Commander: Newcastle upon Tyne Trinity House, 14th June 2016).

Now I have to confess, that although I was of course very much aware of the good Admiral Collingwood and his importance in the development of the Naval Service and indeed this country, I was perhaps not aware of some of his personal traits, much to my own chagrin.

For as one of his sailors wrote of him: “He and his dog Bounce were known to every member of the crew. How attentive he was to the health and comfort and happiness of his crew. A man who could not be happy under him, could have been happy nowhere – a better seamen, a better friend to seaman – a more zealous defender of the country’s rights and honour, never trod the quarterdeck.”

Given the times and harshness of the environment that was some accolade.

He himself also wrote very fondly of the North-East, “Whenever I think how I am to be happy again my thoughts carry me back to Morpeth!”

But I am not here to talk about the good Admiral – I would not be that brave in this company – but the subject of the talk tonight does cross paths with Admiral Collingwood; indeed he was the Admiral who signed the order giving the subject of my talk his first command and seemed to have shared some of the personnel acumen.

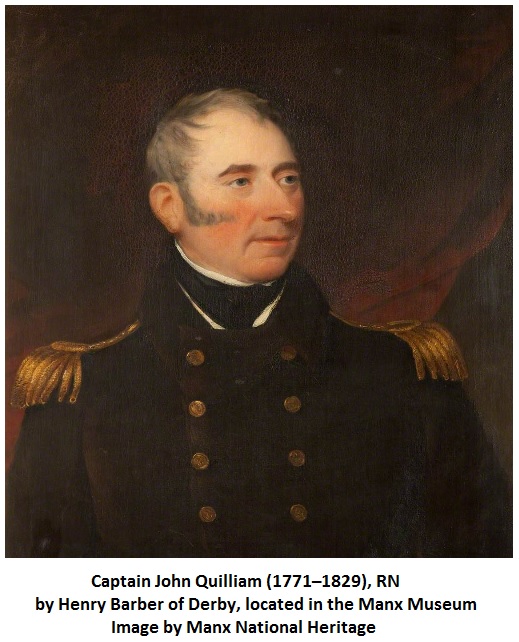

The person I want to talk about is one Captain John Quilliam, Royal Navy, First Lieutenant of HMS VICTORY at the Battle of Trafalgar, a revered Manxman who is buried on the island and recently had a stained-glass window dedicated to him at the church in which he rests (see right).

In researching the subject I must publically acknowledge Professor Andrew Lambert, the noted naval historian, for I have drawn very heavily on some of his research, that being in addition to various online sources.

Rather than start with “John Quilliam was born”… and then recount each step of his naval career, I want to take a ‘Forest Gump’ approach, because in one sense he was a person present in the background of some of the momentous naval engagements of his period, those that shaped the country and indeed the reputations of noted personalities. I will concentrate on four such actions.

I also considered my own current role as a Naval Regional Commander, to see if there are lessons on which we can draw. Indeed there are, or should I say, I think there are. One of the implied tasks I have drawn from my role is to help youngsters who perhaps had not thought about it, to consider service in the Royal Navy or to expand that message somewhat, such that ‘anything is possible with the right application, drive opportunity and encouragement’. And in a sense John Quilliam is a perfect example of that, for his is an interesting story of a man who may have left home penniless because of difficult circumstances, found himself in the Royal Navy as an Able Seaman, seized the opportunities presented to him and with hard work, talent, a good dose of luck of being in the right place at the right time, ultimately rose to the rank of post Captain, making a fortune along the way.

In that sense he is a perfect case study and perhaps inspiration for the youth of today.

Inevitably though, I do need to start at the beginning:

John Quilliam was born at Ballakelly Marown on the Isle of Man on 29th September 1771. He was the eldest of what we think may be six or seven siblings, although some may well have not been pure siblings – I’ll explain later.

His Father was John Quilliam and his Mother Christian Clucas. There is not much record of his early life apart from that I have alluded to already, some interesting snippets from which, depending on your viewpoint, probably explained why he ended up in the Royal Navy.

His father was, we believe, a farmer and his grandfather, who lived near or with them, was the Church Warden. His father was referred to as Captain on the birth certificate of the youngest child, but this as far as I know, has not been substantiated, nor has any further evidence as to the reason for that title been produced.

His grandfather earned a degree of notoriety when their neighbours were presented before the ecclesiastical courts for ‘turning the sieve’ at the Quilliam home. ‘Turning the sieve’ was a form of sorcery for finding the truth of a statement. A few decades on from the hysteria of Salem it may have been, but it was still 18th century Britain, so you can imagine the curtain twitchers!

The families association with the court/quest continued with his father and mother appearing for cursing a neighbour in 1780. Subsequent family transgressions followed, including that detailed on this ecclesiastical record from 1789: “Christian Quilliam, for fornication, a child born, of common fame alleged that her husband is not the father of her child. This women, has said that she has a husband and that is the father of her said child, her censure is there upon suspended until her allegation can be disproved.”

This goes on and although there is record of a daughter of John and Christina baptised in Aug 1792, Christian is again before the courts in Nov 1792 for ‘fornication-child born.’

If the Mother’s morals were brought into question (and of course this may all be grossly unfair and a sign of the times), the father also had his moments for he is recorded as having taking a second wife (obviously common law, as he was still married to Christian). He was also linked to the renowned Manx smuggler Mad Quilliam!

The family farm was also heavily mortgaged and was sold in 1783.

So with a family backdrop of sorcery, fornication, smuggling, debt and mistresses, you could argue that John Quilliam had all the pre-requisites to make a successful career at sea! Or were they rather the reasons…?

Now, there is conjecture on how he joined up in the first place, but the first record we can find is for 15th September 1791, when John Quilliam is recorded aboard HMS LION as a ‘Supernumerary’. This is decidedly interesting for supernumeraries were men over and above the normal strength of the ship who served for victuals only and were not even counted as being in the Navy. They were technically ‘volunteers’, but were often under some personal pressure – people escaping gaol sentences or taking a pardon from offences like smuggling!

But what we do know is that he was not ‘pressed’, for he joined in 1791, which predated the war with France and therefore before the press was sent out.

It possibly indicates he was a well-connected Volunteer. As we will also see his rapid rise to the rank of Petty Officer was probably indicative of skills already obtained as a seaman and someone with career ambitions. A ‘pressed man’ in the late 18th century, particularly without experience, would have no chance of rising to command.

We can draw our own conclusion.

What we do know is that he stayed a Supernumerary until 22 May 1792, when he enlisted as an Able Seaman, still on-board HMS LION, a 64-gun, third-rate ship of the line under the command of one Captain Erasmus Gower.

The relationship with Gower lasted through several ships and indeed eventually saw Quilliam as a Lieutenant – so Gower obviously saw something in him and undoubtedly had a hand in his progression.

At this time Britain’s trade with China was in difficulties. In fact, only the port of Canton was open to European traders and had been so since 1657. Recent modifications to the treaty meant traders were confined to a small area known as ‘the Thirteen Factories’ and had to spend the quiet months in Macao. Trade could only be carried out through the officially designated guild of Chinese merchants, know as ‘Cohong’.

There were no fixed tariff charges and the Cohong extracted what they liked from the foreign traders, who were not permitted to trade or negotiate on any basis of equity. It was also illegal for any Chinese to teach the language to a foreigner.

This prompted the British government to send an embassy to Peking in 1792, in an endeavour to negotiate better terms. HMS LION was the escort.

It is worth diverging slightly to look at the Ambassador they sent – one George McCartney – another interesting character.

Born in Ireland in 1737, he had been a member of both the English and Irish Houses of Commons and held a number of diplomatic posts. He had been captured at Grenada and taken to France as a prisoner of war in 1799. In 1780, he was appointed Governor and President of Fort St. George at Madras by the East India Company and whilst there, he disagreed with the renowned Commanding Officer of the East India Company forces, Major General James Stuart, having him arrested and sent home.

The feud continued and they eventually fought a duel in Hyde Park in July 1786. McCartney was seriously wounded, but recovered, the reason perhaps being that the good General (who had his leg taken away by a cannon ball at the battle of Pollilur) was unable, due to his wounds, to stand unaided for the duel!

McCartney was graciously received in Peking, where he paid homage to the Emperor in Chinese fashion and was admitted to the Imperial Presence. He was very well entertained by the Chinese and, although permission to have a British Minster resident in China at that time was not granted, much information was collected and, as we say in the military, “question 1 was complete and the basis of future negotiations by the British was laid”.

As to John Quilliam, this period in China allowed him to really establish his seamanship knowledge and the mechanics of sailing, so much so that he was rated Quarter Master’s Mate on the 29th April 1795 and, following short appointments on a couple of other ships, he found himself on HMS TRIUMPH, a 74-gun, third-rate – again under the command of Captain Erasmus Gower. Quarter Master’s Mate was essentially a junior Petty Officer – one who still wore sailor’s attire and lived in the mess decks.

The next point in our tour now concentrates on the mutinies of the late 18th century. Still on HMS TRIUMPH, Quilliam was now a Master’s Mate – a senior Petty Officer/Chief in today’s parlance. He had moved from the ‘mess deck’ to the ‘cockpit’ – the senior rates’ mess and was now dressed in a blue frock coat with white trim. He had obviously showed his sailing prowess.

The late 18th century was a time of great unrest in the Royal Navy, following the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1778, when the British fleet under Admiral Jervis, with Nelson as his second in command, defeated the Spanish fleet.

Petitions had been filtering through the Admiralty from sailors, but no notice was taken of them, despite the requests they contained in general being quite reasonable.

The complaints were mostly about pay: 19 shillings per month, less stoppages and no pay when sick, as well as how prize money was distributed.

Others concerned the conditions under which sailors lived, such as gross overcrowded, with no heating, bad food, no proper sanitary facilities and the high rate of infection. Many men were victims of the press gang, whilst others were convicts earning their pardon, all herded together and subject to barbaric forms of discipline.

Mutiny broke out in the channel fleet at Spithead in April 1797 and spread to the fleets anchored in Plymouth and at the Nore in May.

The mutinies differed in character: while the Spithead mutiny was similar to a strike, with only limited violence, the Nore mutiny had more political demands, and was more violent.

To put things in context: Seamen’s pay rates had been established in 1658 and, because of the stability of wages and prices, they were still reasonable as late as the 1756–1763 Seven Years’ War. However, high inflation during the last decades of the 18th century severely eroded the real value of the pay. At the same time, the practice of coppering the submerged part of hulls, which had started in 1761, meant that British warships no longer had to return to port frequently to have their hulls scraped and the additional time at sea significantly altered the rhythm and difficulty of seamen’s work. The Royal Navy had not made adjustments for any of these changes and was slow to understand their effects on its crews. Finally, the new wartime quota system meant that crews had many ‘landsmen’ from inshore who did not mix well with the career seamen, leading to discontented ships’ companies.

The mutineers at Spithead were led by elected delegates and they tried to negotiate with the Admiralty for two weeks, focusing their demands on better pay, the abolition of the 14-ounce “purser’s pound” (the ship’s purser was allowed to keep two ounces of every true pound—16 ounces—of meat as a perquisite) and the removal of a handful of unpopular officers. Of note, neither flogging nor impressment was mentioned in the mutineers’ demands. The mutineers maintained regular naval routine and discipline aboard their ships (mostly with their regular officers), allowed some ships to leave for convoy escort duty or patrols and promised to suspend the mutiny and go to sea immediately if French ships were spotted heading for English shores.

Because of mistrust, especially over pardons for the mutineers, the negotiations broke down and minor incidents broke out, with several unpopular officers sent to shore and others treated with signs of deliberate disrespect. When the situation calmed, Admiral Lord Howe intervened to negotiate an agreement that saw a Royal Pardon for all crews, reassignment of some of the unpopular officers, a pay raise and abolition of the purser’s pound.

As a direct result of the mutinies at Spithead and The Nore, many of the worst abuses prevalent in the Royal Navy up until this time, such as bad food, brutal discipline and the withholding of pay, were remedied.

The Nore was an entirely different affair, being more serious in its actions. Here, it had to be put down by force. It is also of note that, as matters developed, some of the mutinous ships at the Nore actually chose to sail and re-join the fleet – coming under fire from their erstwhile comrades as a consequence.

In the aftermath, twenty-nine sailors were executed, including the ringleader Richard Parker, who was tried for treason and piracy and hanged from the jib of HMS SANDWICH, the ship on which he had mutinied. Several men were deported to Australia, whilst others were severely flogged.

Amongst the familiar names was one of an officer who had the dubious record of being present at three mutinies – The Nore, New South Wales and his own Ship HMS BOUNTY – Captain William Bligh!

Another piece of trivia after the Nore mutiny, explains why Royal Navy vessels no longer rang five bells in the last dog watch, since that had been the signal to begin the mutiny.

During the Nore episode, we were not only at war with the French but their Dutch allies were also restless and threatening the North Sea.

Admiral Duncan, whose job it was to blockade the Dutch fleet of some twenty ships in Texel, sailed from the Nore with two loyal ships and spent days confusing the Dutch with flag signals to imaginary ships over the horizon. He was eventually joined by HMS TRIUMPH (with Quilliam aboard) and other ships and the Battle of Camperdown eventually ensued.

The Dutch were roundly defeated and Master’s Mate Quilliam excelled so much that he was rated as Acting Lieutenant, a post he held for a month.

Returning for a moment to the mutiny, we can establish Quilliam and HMS TRIUMPH were indeed at Spithead. An address from the sailors at Spithead to their brethren at the Nore calling them to resume duties was signed by two representatives from HMS TRIUMPH. Captain Gower also played a large part in ending the mutiny and was included in the court martial team.

Following the mutiny and Camperdown, things were about to change for Quilliam.

In May 1798, just three days after the requisite six years’ service, his application for examination for the rank of Lieutenant was submitted. Successful, he was promoted on the 6th October 1798.

As a Lieutenant he had a rapid succession of ships, with only service on the Frigate HMS ETAHLIAN in 1799 standing out, for this is where he made his fortune following the capture of the Spanish treasure ship THETIS.

The resulting prize money was:

40,000 for the Captain

5,000 each for the Lieutenants

2,500 for the Warrant Officers

791 for the Midshipmen

and 182 for the Seaman

To put that in context into today’s values, for Quilliam it was over 3 million pounds. He had suddenly become a rich man.

I will not dally on his money or what he did with it save to say he bought property and relieved his families’ mortgages, but jump forward to the next momentous event.

In March 1800, Quilliam was commissioned to the frigate HMS AMAZON as a Lieutenant. The Captain was one Edward Riou, described as ‘having a scholarly countenance shaded by a pleasing gloom’

HMS AMAZON was transferred to the North Sea and Baltic fleet in preparations for operations against the Danes. The fleet sailed on 12th March under the command of Sir Hyde Parker and Vice Admiral Lord Nelson.

On arrival at the outer reaches of Copenhagen harbour, Nelson transferred to HMS AMAZON to reconnoitre the channel. Nelson was obviously impressed by AMAZON and her Captain, for they were given the role of leading the squadron of frigates right in to attack the batteries located at the Trekroner fortress. The line of battle ships meanwhile, led by Nelson’s Flag ship HMS ELEPHANT, dealt with the Danish fleet and Admiral Parker remained in reserve in the outer reaches to protect the flank against Russian interference.

There are a couple of things worth looking at here and perhaps taking the opportunity to correct a few myths: Because of the shallow depth around Copenhagen, Admiral Parker had allocated Nelson the shallowest drafted Line ships – Nelson himself transferred his flag from the larger 96-gun HMS ST. GEORGE to the smaller 74-gun and shallower draft HMS ELEPHANT. As battle commenced and as ever with the shallow water as a contributory factor, there was a degree of confusion. Three line ships ran aground before bringing their guns to bear.

Admiral Parker could see little of the battle owing to gun smoke, but could see the signals on the three grounded British ships, with BELLONA and RUSSELL flying signals of distress and AGAMEMNON a signal indicating her inability to proceed.

Thinking that Nelson might have fought to a stand-still but might be unable to retreat without orders (the Articles of War demanded that all ranks ‘do their utmost’ against the enemy in battle), at 1:30pm Parker told his flag Captain, “I will make the signal of recall for Nelson’s sake. If he is in condition to continue the action, he will disregard it; if he is not, it will be an excuse for his retreat and no blame can be imputed to him.”

Nelson ordered that the signal be acknowledged, but not repeated. He turned to his flag Captain, Thomas Foley, and said “You know, Foley, I only have one eye — I have the right to be blind sometimes,” and then, holding his telescope to his blind eye, said “I really do not see the signal!” Rear Admiral Graves repeated the signal, but in a place invisible to most other ships while keeping Nelson’s ‘close action’ signal at his masthead. Of Nelson’s captains, unfortunately only Riou at the head of the frigate force, who could not see Nelson’s flagship HMS ELEPHANT, followed Parker’s signal. Riou withdrew his force, which was then attacking the Trekroner fortress, exposing himself to heavy fire.

Returning to the action on the AMAZON, she too received a devastating shot through the stern from the batteries, that not only left the ship badly damaged but cut the Captain in two and killed all the senior officers, leaving Lt Quilliam in command.

According to A W Moore in ‘Manx Worthies’, this is where Quilliam first came in contact with Nelson and I quote from his book:

“All Quilliam’s superior officers were killed, so that he was left in command. At this juncture, Nelson came on board and enquired who was in charge of her, when a voice, that of Quilliam, ascended from the main deck, ‘I am’ and on the further question ‘How are you getting on below’ the answer to the unknown inquisitor was ‘middlin’. This greatly amused Nelson, who so appreciated Quilliam’s coolness that he took an early opportunity of getting him on his own ship HMS VICTORY, of which he was appointed First Lieutenant.

It is a pity to spoil a good story, but if this is supposed to have happened during the battle there are obviously some flaws – not least of them was that Nelson was some distance away, fully engaged trying to persuade the Danes to surrender.

However of course, it could be just that the reported timing was out. It is known that the following day Nelson visited BELLONA and that he enquired about Captain Riou, so he may well have visited AMAZON.

Regardless, Quilliam rose to the challenge under difficult conditions under fire and came to the attention of his superiors.

The subsequent Captain of HMS AMAZON, Captain Sam Sutton, was a confident of Nelson and they corresponded regularly.

It is also of interest here that Nelson summoned Captain Bligh to thank him for ‘his admirable support during the action’.

After a period at home on the Isle of Man, Quilliam found himself appointed to HMS VICTORY on 4th April 1803, then also under the command of Sam Sutton and preparing for sea.

On arrival off Toulon in July of that year, having seized a French frigate and two or three ships from San Domingo along the way, Nelson and Captain Hardy transferred to HMS VICTORY with Captain Sutton moving to HMS AMPHION.

There is evidence that Nelson struck up a positive relationship with Quilliam during this period. So much so, that there were apparent mutterings amongst those officers junior to Quilliam. I can perhaps add my own view here – the relationship between a Captain and his First Lieutenant is crucial, especially when fighting, at which time they effectively need to be in each other minds. I know mine with my First Lieutenant started to border on the telepathic – he knew exactly what I would do in a given situation. Now whilst Nelson was an Admiral, he was instrumental in deciding where HMS VICTORY went, so he need to not only appreciate how Hardy ticked – Quilliam as the First Lieutenant was crucial in manoeuvring and operating the ship. So this relationship was not unsurprising.

Again I will not touch on the battle, but rather two incidents involving our good Lieutenant, one during and one after the action.

Early in the battle, long before HMS VICTORY had fired a shot, she had sustained considerable damage. The following account reports the detail:

‘Just as she (the VICTORY) had got about 500 yards off the larboard beam of the BUCENTAURE, the VICTORY’s mizzen – topmast was shot away, which knocked to pieces the wheel; when the ship was obliged to be steered from the gun room, the First Lieutenant, Quilliam, and Master (Thomas Atkinson) relieving each other at the duty’.

So it came about the saying that Quilliam “steered” the VICTORY in the Battle of Trafalgar.

Quilliam had apparently supervised the rigging of the tackles and had stayed to ensure it worked properly, which is probably closer to the truth. But this still required his quick thinking and seamanship acumen to make it work.

Another account that cemented Quilliam’s reputation during the battle relates to the moment Nelson died, for when Nelson breathed his last someone hauled down the Admiral’s flag. Quilliam, seeing this, hoisted it again. Evidently he did not wish our own men to be disheartened, nor the enemy encouraged.

It is opined by people that it is the events of these few hours and days that made Quilliam the Manxman’s Hero. The stories about him appear to have been in part the work of others. He himself appears to have kept silent, even to the point of not correcting erroneous statements printed during his life time. He spoke about these things only to his closest friends.

Personally, I am sure he is not alone then or today and the truth will be somewhere in between, but as First Lieutenant, he will undoubtedly have been the hub of the wheel, excuse the pun, and would have been here, there and everywhere, so why not credit him for the actions?

Regardless of these varying opinions, First Lieutenant Quilliam was instrumental in the recovery of HMS VICTORY to Gibraltar after the battle. It is here that he came to the attention of one Admiral Collingwood, as you know second in command to Nelson during the battle and a very close friend of the good Horatio. Again although it was traditional for First Lieutenants to receive promotion after a successful action, I think history shows that it was deserved.

On the 22nd October 1805, he was promoted Commander and appointed in command of Her Majesty’s Bomb AETNA by Cuthbert Collingwood, Esq. But his time in this rank and with this ship was short lived and indeed a bit remarkable, for he was promoted Post Captain on 24th Dec and transferred to the SAN ILDEFONSO – one of the prizes taken at Trafalgar. She was in a poor state and required all his leadership and seamanship knowledge to return the vessel to the fleet and sail back to Britain.

As I say making post so quickly (and it had been reported inaccurately that he jumped direct to Post from Lieutenant) was unusual and we can attribute that to his deeds at both Trafalgar and Copenhagen.

Why is this significant? Making Post was an important and significant step, for once an officer had been promoted to Post Captain, his further promotion was strictly by seniority; if he could avoid death or disgrace, he would eventually become an Admiral.

Quilliam would serve a further ten years in the Royal Navy, commanding four ships – two line ships including as Flag Captain to Admiral Stopford aboard the 74-gun HMS SPENCER, after which he was selected for Frigate command. Before moving to this later phase in his career, it is worth looking at his time in SPENCER.

Stopford was promoted Rear Admiral on 28th April and Quillaim was appointment to the SPENCER as Flag Captain on the 12th May, I suspect at Stopford’s request. The Squadron was responsible for blockading Rochefort and was repeatedly in action, being engaged both with the French batteries and frigates, several of which were driven ashore and destroyed.

It was during this time in command that we are able to draw on some of his correspondence, which provides an insight to the man.

The first example points to his care for his men:

‘Sir,

I have to request you will be pleased to state to My Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty that John Milling a seaman belonging to His Majesty’s Ship under my command who gave himself up as a deserter from the Army, states, that his only reason for declaring himself to be such was to avail himself of the pardon offered to deserters in His Majesty’s late proclamation; and as the said man is a good seaman, I beg that their Lordships will be pleased to allow him to remain on board SPENCER.

I have the honour to be sir, your obedient servant, John Quilliam’.

The second alludes to his technical prowess:

‘Sir,

His Majesty’s Ship SPENCER under my command being, from her construction and straight sides, much inclined to stoop to her canvas; I beg leave to suggest to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty whether a doubling of six inch plank upon her bottom might not in some measure remedy this important defect and should it meet Their Lordships approbation I have to request they will be pleased to direct it being carried into execution at the time the ship is in dock.’

Indeed, both interesting and illuminating extracts.

Returning to frigate command: to secure the appointment of frigate command in the Royal Navy in the last decade of the Napoleonic conflict was the highest commendation of a Post Captain’s intelligence, capacity for independent operations, seamanship, tactical acumen and determination.

These frigate commands were important appointments, including duties such as escorting convoys between the east coast of Britain and the Baltic and joining the Newfoundland Station, where he cruised in defence of British merchant ships during the war of 1812. One of these frigates, HMS CRESCENT, was one of the first ships to test the new iron mooring chains and patent sail cloth.

These appointments indicated Quilliam was recognised as an experienced seaman and an effective team builder and leader. There is also evidence in his correspondence from this time, as we saw from SPENCER, that, like Collingwood, he had a great empathy with his men. He fought for those that deserved it and dished out just deserts to those who let him down. He would for example be engaged with pay, prize money and preferment for old shipmates for several years after he retired.

The end of the long wars in 1815 saw John Quilliam request to be placed on the half pay list. It was a fitting end to a 24-year career at sea and at the age of 44, he was the oldest frigate Captain afloat.

After coming ashore for the last time, Quillaim returned to the Island he loved and joined the House of Keys, which he attended regularly. He also worked his not inconsiderable portfolio of properties and investments. He slipped away on the 10th October 1829, aged 58.

You will appreciate it is difficult in just a few words to do justice to a character such as Quilliam. I have for example not touched on his time on the Isle of Man. But if we return to what I said at the outset, my intent was to canter through some of the momentous events of the late 18th and earlier 19th century that Quilliam found himself in and to demonstrate that with a bit of luck and hard work, many things are possible.

(The Collingwood Society gratefully acknowledges Commodore Doyle’s kind permission to reproduce the text from his talk).