At frequent intervals since 1805, the argument as to whether Collingwood made the right choice after the Battle of Trafalgar is re-run. This of course relates to his decision to deliberately sacrifice a number of prizes and for the fleet to run for Gibraltar in the midst of a gale.

Those who support the Admiral’s position point to aspects of basic seamanship: the principle of not anchoring on a lee shore in the face of a coming storm and the realised or likely inablility of many of the ships, severely damaged in battle, to anchor anyway. Those who decry his decision point to the loss of the ships (and their crews) and the significant negative impact that had on the levels of much-needed prize money awarded to the survivors. They also point to Nelson’s words, uttered shortly before his death, in which he is reported to have issued instructions for the fleet to anchor which if true and known to Collingwood, he chose to disregard.

As part of the 2010 programme of the North-East Branch of the Nautical Institute and integrated into the calendar of the Collingwood 2010 Festival, Dr. Dennis Wheeler, an expert on the weather of Trafalgar from the University of Sunderland, made a fascinating presentation on the Great Storm and the meteorological information that would have been available to Collingwood, his officers and indeed those on the Spanish and French ships, Dr. Wheeler speaks from a position of considerable knowledge and expertise, having studied the meteorological entries in the log books of thousands of ships, particularly those of naval vessels, as part of the CLIWOC (Climatological data for the World’s Oceans 1750 – 1850) Project.

It was indeed interested to learn how detailed the information was and how close it was to the equivalent data recorded today. Indeed, the point was made that the average seamen in 1805 was a sight more “tuned-in” to the weather than his modern counterpart, technology aside.

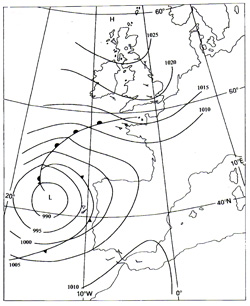

From the available information, drawn from English and Spanish ships, as well as the observations of a number of shore stations, significantly including the Real Observatorio de la Armada, Cadiz, Dr. Wheeler has compiled a detailed weather picture for the 21st October 1805. The day dawn calm and it is well known that from the first sightings at daybreak, it took until midday for the two fleets to close. During the battle, the weather began to turn and it is said that the mortally wounded Nelson, lying on the orlop deck of HMS Victory, felt the increased movement of the ship in the rising swell, prompting his concerns.

Dr. Wheeler is entirely confident that Collingwood would have seen the changing weather and correctly assessed the severity of the coming gale, estimated the time the sea and wind conditions would take to worsen and would have fully realised the impact that the storm might have on the fate of the ships. This despite all the other management decisions required of him in the aftermath of that huge sea battle. Indeed, his order to get as far off the coast as possible before it became necessary to reduce sail might be seen as an entirely sound decision based on pure seamanship and possibly one of the easier decisions to make.

What neither he, nor anyone else, would (and could) have realised was the duration of the coming gale, as there was no long-range information from out in the Atlantic ocean available, such as would be provided by satellite images today. On the basis of his experience and knowledge of those waters at that time of year, he would most likely have believed that it would last around 48 hours at the most. He would therefore have considered that the majority of the ships were capable of riding it out, given sufficient distance off the shore to begin with. In fact, it lasted for the best part of a week and was truly the meteorological event of the first half of the century in north-east European waters.

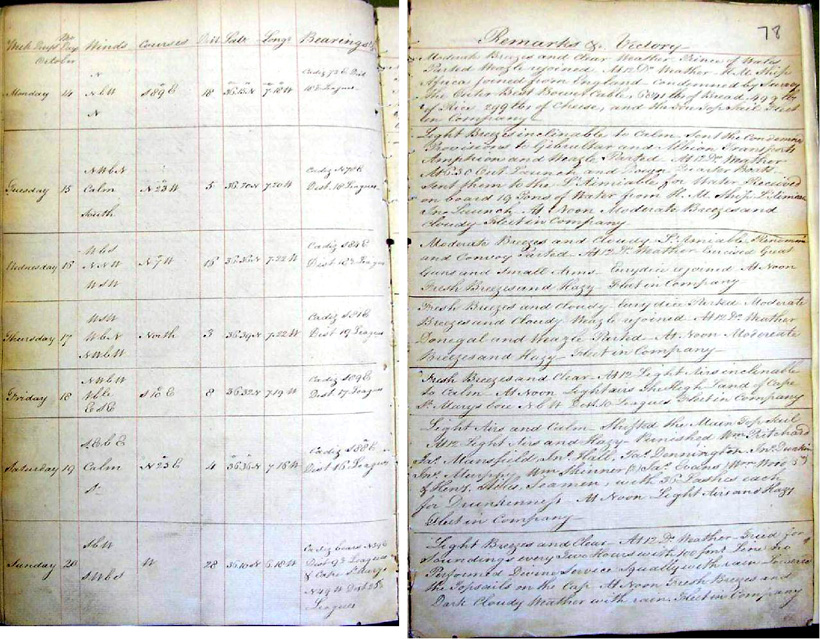

To the great interest and slight amusement of many in the audience, Dr. Wheeler produced as part of his presentation what would have been the Shipping Forecast for the morning of 21st October, along with the weather map for the region. With his kind permission they are reproduced below, along with an extract from the logbook of HMS Victory, written by Captain Thomas Masterman Hardy.

In conclusion, it was demonstrated that Collingwood remained entirely focused on the mission, drawing on the following extract from his despatch to the Admiralty, written immediately after the battle: “The storm, being so violent, and many of our ships in most perilous situations, I found it necessary to order the captures, all without masts, some without rudders, and many half full of water, to be destroyed, except such as were in better plight; for my object was their ruin and not what might be made of them.”

THERE ARE WARNINGS OF GALES IN PORTLAND, PLYMOUTH, BISCAY, FITZROY, TRAFALGAR AND SOLE

THERE ARE WARNINGS OF GALES IN PORTLAND, PLYMOUTH, BISCAY, FITZROY, TRAFALGAR AND SOLE

THE GENERAL SYNOPSIS AT 0800

LOW TRAFALGAR 985 MOVING SLOWLY SOUTH EASTWARDS DEEPENING 980 BY SAME TIME TOMORROW HIGH FAIR ISLE 1030

THE AREA FORECASTS FOR THE NEXT 24 HOURS

VIKING NORTH UTSIRE SOUTH UTSIRE FORTIES

N OR NE 3 OR 4. MODERATE

CROMARTY FORTH TYNE

N OR NE 2 OR 3. MODERATE

DOGGER FISHER GERMAN BIGHT HUMBER

NE 3 OR 4. MODERATE

THAMES DOVER WIGHT

NE 4 OR 5 INCREASING 6 OR 7 LATER. MODERATE OR GOOD

PORTLAND PLYMOUTH

E 5 OR 6 INCREASING 7 GALE 8 LATER. RAIN OR SHOWERS MODERATE OR POOR

BISCAY

E OR SE 4 INCREASING 6 OR 7. MODERATE OR GOOD

FITZROY SOLE

E OR SE 5 OR 6 NE IN WEST FITZROY INCREASING 7 GALE 8 LATER. RAIN MODERATE

TRAFALGAR

SW 1 OR 2 INCREASING 5 OR 6 VEERING WEST BECOMING GALE FORCE 8 LATER. GOOD BECOMING MODERATE OR POOR RAIN LATER

LUNDY FASTNET IRISH SEA SHANNON

E OR SE 4 OR 5 INCREASING 6. MODERATE

IRISH SEA MALIN ROCKALL

SE 2 OR 3. MODERATE

BAILEY FAROES SOUTH EAST ICELAND

VARIABLE 1 OR 2. MODERATE OCCASIONALLY POOR

Extract from the logbook of HMS Victory for 21st October 1805, including observations of wind force and direction, as well as narrative entries on the changing conditions “Light winds and squally with rain. At 2 taken aback…” and “…at 8 light breezes and cloudy.”